Zu dem SZ-Gastbeitrag „Die Bedrohung der Wissenschaftsfreiheit gefährdet die Demokratie“ (Nassehi & Tschöp 2025), hier eine Kritik in zehn Punkten.

Vermischung normativer und analytischer Argumente

Der Text springt zwischen moralischer Empörung („Angriff auf die Wissenschaftsfreiheit“) und theoretischer Begründung (Bezug auf Weber, Jaspers) hin und her. Dadurch bleibt unklar, ob die Autoren nun eine soziologische Analyse liefern oder eine politische Stellungnahme formulieren wollen. Dieser Zickzack Kurs schwächt die argumentative Klarheit. Eine klare Trennung der analytischen Ebene „Welche gesellschaftlichen Mechanismen bedrohen Wissenschaftsfreiheit?“ und des normativen Teils: „Warum sie für Demokratie unverzichtbar ist?“ mit Beleg durch empirische Beispiele oder Forschung wäre überzeugender gewesen.

Zirkularität der Hauptthese

Die Kernbehauptung lautet sinngemäß daß „Wissenschaft nur in Freiheit gedeihen kann und Freiheit gibt es nicht ohne Wissenschaft.“ Das ist logisch zirkulär, denn es wird nicht gezeigt, warum denn Freiheit nun zwingend von Wissenschaft abhängt. Die Behauptung steht tautologisch im Raum, ohne empirische oder historische Belege. Überzeugend wäre gewesen, warum Freiheit für Wissenschaft nötig ist (methodische Offenheit, Peer Review, Kritikfähigkeit, Weiterentwicklung). Und dann liesse sich auch unschwer empirisch zeigen, daß wissenschaftliche Rationalität demokratische Verfahren stärken kann (z. B. evidenzbasierte Politik, deliberative Öffentlichkeit) und eine gegenseitige Abhängigkeit entsteht. Alles andere ist die aufgeblähte Rhetorik einer Proseminar Arbeit.

Übertragungsfehler auf allgemeine Demokratietheorie

Die Erregung mag ja nun verständlich sein an der grössten deutschen Universität. Der Artikel stützt sich auf die US-Politik unter Trump/Kennedy, zieht daraus aber weitreichende Schlüsse über Demokratien im Allgemeinen. Der Übergang von einem spezifischen und zugegeben unangenehmen Fall zu einer universellen Diagnose („auch hierzulande droht Gefahr“) bleibt unbegründet. Besser wäre ein komparativer Vergleich gewesen statt der praktizierten Erregungskultur: Beispiele aus Polen, Ungarn, Brasilien, Türkei zeigen das Muster von politischer Instrumentalisierung zu Einschränkung der Autonomie über den Vertrauensverlust bis hin zur “Demolierung der Demokratie”.

Idealisiertes Wissenschaftsbild

Die Autoren zeichnen ein idealisiertes, fast schon sakrales Bild von Wissenschaft („Fakten bleiben bestehen, auch wenn alles Wissen vernichtet wird“). Damit werden methodische und institutionelle Fehlbarkeit weitgehend ausgeblendet – z. B. Machtstrukturen, Gender Bias, Publikationszwänge, Reproduzierbarkeitskrise. Der Text reflektiert zwar kurz „Selbstkritik“, aber nur oberflächlich und mehr pflichtschuldig. Wissenschaft sollte realistischer als soziales System mit Fehlanreizen, Macht, Hierarchie und Interessen beschrieben werden. Gerade weil Wissenschaft fehleranfällig ist, braucht sie Freiheit zur Korrektur.

Mangelnde Differenzierung von „Freiheit“

„Wissenschaftsfreiheit“ wird als absoluter Wert dargestellt, ohne zwischen äußerer Freiheit (also vor politischer Zensur) und innerer Freiheit (etwa durch ökonomische, institutionelle oder soziale Zwänge) zu unterscheiden. Die Autoren erwähnen zwar die „Schere im Kopf“, analysieren diese aber nicht weiter – das Argument bleibt im luftleeren Raum stehen.

Appell statt Argumentation

Große Teile des Textes bestehen aus Appell- und Bekenntnisrhetorik („Wir haben viel zu verlieren“). Es werden kaum Belege, empirische Beispiele oder Gegenargumente präsentiert. So ist der Beitrag dann doch eher Plädoyer mit Pathos im Schlussabschnitt – um Wirkung zu entfalten, aber nicht um rational zu überzeugen.

Widerspruch zwischen Selbstkritik und Autoritätsanspruch

Am Schluss fordern die Autoren zwar „mehr Selbstkritik“ und „wissenschaftliche Klärung“ ein, ohne aber ihre eigenen normativen Prämissen zu hinterfragen. Das schwächt den Anspruch *wissenschaftlich* über Wissenschaft zu sprechen. Es ist eine verpasste Chance, explizit die eigenen institutionellen Rolle reflektieren, wie sie an der Spitze des Wissenschaftsbetriebs profitieren von Macht und Geld und Strukturen, die Kritik erschweren.

Fehlende Auseinandersetzung mit legitimer Wissenschaftskritik

Un nicht zuletzt: Die „Elitenkritik“ wird erwähnt, doch die Autoren behandeln sie vor allem als Gefahr, nicht als möglicherweise berechtigte gesellschaftliche Rückmeldung. Dadurch wirkt der Text selbst elitär – ein blinder Fleck im Hinblick auf das von ihnen geforderte „Vertrauen in Wissenschaft“. Vertrauen sollte nicht nur gefordert, sondern muss verdient werden.

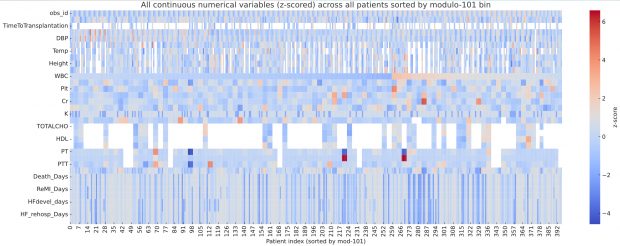

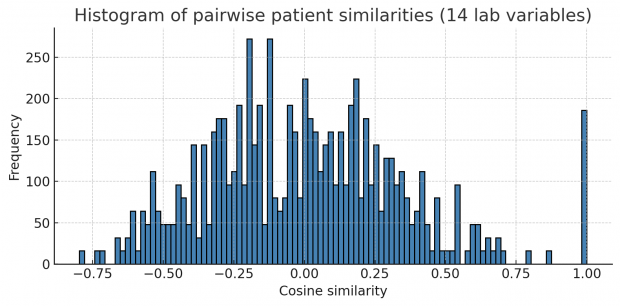

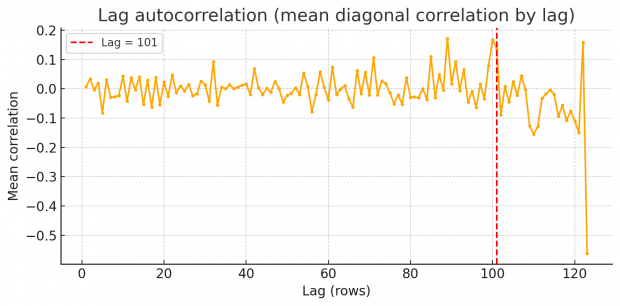

Wissenschaftliche Unredlichkeit wird ignoriert

Übersehen wird dabei die eigentliche Vulnerabilität der Wissenschaft – die Faulgase im Inneren des Systems: erfundene Daten und gefälschte Grafiken, Plagiate und mehrfach verwertete Daten, Zitierkartelle, Paper Mills und nicht zuletzt hochgradig selektive Darstellungen als Ursache der Replikationskrise. All das unterwandert die Idee wissenschaftlicher Redlichkeit von innen heraus und bedrohen ihre Glaubwürdigkeit weit stärker als der gesellschaftliche Erwartungsdruck, vor dem die Autoren warnt.

Finis

Der Text stammt offensichtlich von Nassehi; von Tschöp sind bisher nur Versuchsbeschreibungen von übergewichtigen Mäusen überliefert. Frühere Nassehi Rezensionen haben angemerkt, dass er zuweilen in einer stark theoretischen und abstrakten Weise argumentiert – etwa in seinen Überlegungen zur digitalen Gesellschaft, wo weitreichende Thesen formuliert werden, ohne auf eine solide empirische Fundierung zurückzugreifen. Charakteristisch ist sein wiederholter Appell an ein gesteigertes Bewusstsein für Komplexität, Ambiguität und Perspektivendifferenz, verbunden mit einer Skepsis gegenüber „großen Gesten“. Paradoxerweise verfällt er jedoch in diesem Text selbst in eben jene rhetorische Haltung, vor der er sonst gerne warnt.

(verfasst mit chatGPT 5 Support)

Postscriptum

Und was ist eine der ersten Amtshandlungen des neuen Präsidenten, nur zwei Wochen nach der Inauguration? Nach Kritik aus der CDU und einer Interessengruppe an einer geplanten Veranstaltung kommt nun diese Pressemitteilung heraus “LMU als Ort des pluralistischen Diskurses”

Zu dem an der LMU geplanten Seminar „The Targeting of the Palestinian Academia“ hat die Hochschulleitung sich mit dem Veranstalter Professor Andreas Kaplony, Lehrstuhl für Arabistik und Islamwissenschaft, ausgetauscht. Hierbei wurden sowohl der wissenschaftliche Charakter der Veranstaltung als auch Sicherheitsbedenken erörtert. Daraus resultierte folgende einvernehmliche Vorgehensweise:

- Die für den 28.11.2025 terminierte Veranstaltung findet nicht statt.

- Zeitnah werden Professor Kaplony, Mitglieder der Hochschulleitung und der Fakultät für Kulturwissenschaften damit beginnen, geeignete wissenschaftliche Formate auch für derart aufgeladene Themen zu entwickeln.

- Ein solches Format soll in absehbarer Zeit umgesetzt werden.

Die LMU hat sich die Entscheidung nicht leicht gemacht und die relevanten wissenschaftlichen und rechtlichen Aspekte abgewogen. Die Freiheit der Wissenschaft ist ein hohes Gut, es bestanden in diesem Fall aber Zweifel, ob es sich um eine wissenschaftliche Veranstaltung auf dem erforderlichen Niveau gehandelt hätte. Die LMU trägt dabei ihrem Anspruch Rechnung, die Freiheit der Wissenschaft, die freie Rede, die sachliche Austragung von Konflikten, sowie Respekt gegenüber unterschiedlichen Auffassungen zu leben.

Was auch immer auf dieser universitären Veranstaltung hätte diskutiert werden sollen, ob hier womöglich zu Rechtsbruch aufgerufen worden wäre, das kann ich alles nicht sagen. Aber wir können festhalten, daß die Pressemitteilung behauptet, die LMU sei ein „Ort des pluralistischen Diskurses“, aber gleichzeitig eine geplante Diskussion absagt. Sie betont die „Freiheit der Wissenschaft“, knüpft diese jedoch an eine interne Bewertung des „wissenschaftlichen Niveaus“ – und schränkt damit gerade jene Freiheit ein, die vor wenigen Monaten noch so hoch gehalten wurde.

Die jüngsten Attacken der US-Regierung gegen die Universitäten sind nicht weniger als ein Angriff auf die Wissenschaftsfreiheit. Das ist eine ernst zu nehmende Gefahr. Denn Wissenschaft kann nur in Freiheit gedeihen.

Anstatt Debatten zu ermöglichen, wird der Diskurs verschoben und durch unbestimmte, zukünftige Formate ersetzt. Sicherheits- und Qualitätsargumente dienen dabei als Vorwand, kontroverse Inhalte nicht zuzulassen. So hat die Pressemitteilung das fatale Ergebnis, dass sie Offenheit verspricht aber faktisch Wissenschaftsfreiheit unterläuft.

CC-BY-NC Science Surf

accessed 11.03.2026